Pink Floyd, das 1965 von vier Schulfreunden in Cambridge, England, gegründete Schrittmacher-Quartett des elektronischen Rocks, bestanden zunächst aus dem Sänger und Leadgitarristen Syd Barrett (geboren am 6. Januar 1946 in Cambridge), dem Bassgitarristen und Sänger Roger Waters (geboren am 6. September 1944 in Great Bookham), dem Pianisten und Organisten Rick Wright (geboren am 28. Juli 1943 in London) und dem Schlagzeuger Nick Mason (geboren am 27. Januar 1945 in Birmingham).

1968 wurde Barretts Part von David Gilmour (geboren am 6. März 1946 in Cambridge) übernommen. Anders als die meisten Rockbands, die ihren Gitarrenverstärkern in der Regel nur simples Rückkopplungsgeheul entlockten, erschlossen Pink Floyd – drei von ihnen hatten am Londoner Polytechnikum studiert – das ganze Arsenal elektronischer Sinustöne und Sägezahnklänge für die Popmusik. Mit den Science-fiction-Hörbildern ihrer Stücke A Saucerful Of Secrets, Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, Astronomy Dominé und Interstellar Overdrive, zu denen sie im Londoner UFO-Club fantastische Lichtshows zelebrierten, “rockten und rollten” sie 1967/68 “in eine neue Musizier-Epoche” (“The Observer”). Wo sie ihren sogenannten Azimuth Koordinator aufstellten, schrien Möwen, plätscherte Wasser, ratterten Maschinengewehre, dröhnten Düsenflugzeuge, explodierten Bomben: Mit dem komplizierten, siebenkanaligen 360-Grad-Misch- und Steuersystem ließen sich all diese Geräusche von Tonbändern einspielen oder instrumental imitieren. Durch Lautsprecher, die an allen vier Seiten der Konzertsäle angebracht waren, ermöglichte der Koordinator raffinierte Echowirkungen und einen vollendeten Quadro-Raumeindruck. Die Musik, empfand der Kritiker Tony Palmer, “scheint von deinem Nebenmann, von der Decke, von unter dem Sitz zu kommen, manchmal sogar aus deinem eigenen Gehirn”. Das Jazzmagazin “Down Beat” in den USA bewunderte die “superbe Kontrolle der Strukturen und Effekte”; die “New York Times” lobte “eine Lebendigkeit, der klassische Elektronikwerke oft ermangeln”. Die Anerkennung aus dem E-Musik-Lager und aus den internationalen Feuilletons verführte die Gruppe jedoch bald zu eklektizistischen Imitationen seriöser Konzertmusik und zur Gigantomanie. Die Dominantseptakkord-Reihen aus Bachs g-Moll-Präludium, mit mulmigem Schwellorgelklang intoniert, kehrten in ihren Stücken fortan häufig wieder. Mit dem aufwendigen Chor- und Orchesterwerk Atom Heart Mother gelang ihnen nur mehr “eine substanzlose Melange” aus Aaas und Ooos, aus Yeah und Sasasasa – “im Ganzen schmalzig und ein wenig schal” (“Rolling Stone”). Spielfilme wie Antonionis “Zabriskie Point” und eine amerikanische Cartoon-Fernsehreihe waren mit dem Sphärengetön vortrefflich zu untermalen.

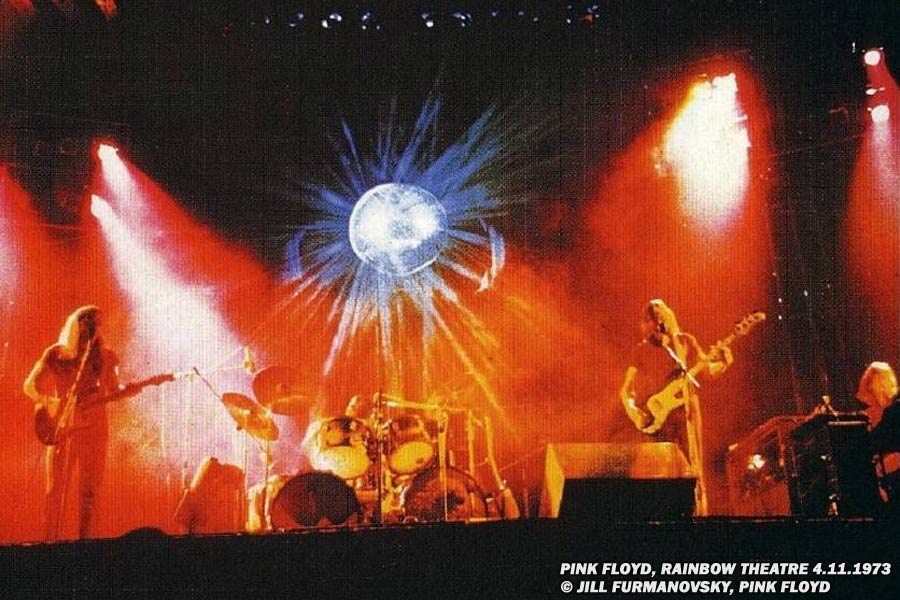

Ihren größten Kommerzerfolg lancierten Pink Floyd 1973 mit dem “Rock-Meisterwerk” (Irwin Stambler) Dark Side Of The Moon, einem düsteren Tongemälde über die Pressionen des Alltagslebens und die Reaktionen darauf: Entfremdung, Verdrängung, Schizophrenie. Alle Texte stammten von Waters. Für die instrumentalen Überleitungen zwischen den Songs kamen alle Sound-Experimente aus den vorausgegangenen LPs Meddle (1971), Obscured By Clouds (1972) konzentriert zur Anwendung. 1980 brach die LP den vorherigen Rekord von Carole Kings Tapestry als Longseller (302 Wochen) in den Billboard-Charts. Nach 15 Jahren wurde die LP unter den Top 100 immer noch geführt – 1988 in der 700. Woche. Bis 1994 war sie 13Millionen Mal verkauft worden. Die Gigantomanie auf den Bühnen der Dark Side sowie die auf den folgenden LPs Wish You Were Here (1975) und Animals (1977) begleitenden Tourneen wurde eher noch größer. Riesige Puppenmonstren überragten die Bühnen von Open Air-Stadien mit Kapazitäten von 40000 bis 50000 Besuchern. Filmprojektionen umrahmten die Bühnenaktion in geschlossenen Hallen.

1979 gelang den Musikern – Gilmour und Wright hatten inzwischen ihre ersten Solo-LPs veröffentlicht – mit The Wall ein weiterer großer Wurf. Thema blieb die Isoliertheit und Bedeutungslosigkeit des (jungen) Menschen in der Massengesellschaft: “Nur ein weiterer Stein in der Mauer.” Obgleich die Single Another Brick In The Wall von Rundfunksendern wie der BBC boykottiert wurde, etablierte sie sich als erste kleine Platte der Gruppe beiderseits des Atlantik auf Platz eins. Die LP belegte 15 Wochen lang die erste Chartsposition und wurde in dieser Zeit mehr als Achtmillionenmal verkauft. Auflage 1995: zehn Millionen. Für Konzerte mit The Wall schwoll der Bühnenaufwand nach den Wünschen der Musiker derart an, daß die volle Show nur in London, New York, Los Angeles und Dortmund gezeigt werden konnte. Über die ganze Bühnenbreite wurde eine Mauer errichtet, die auf dem Höhepunkt des Geschehens in sich zusammenfiel. Das Spektakel hatte 1982 Alan Parker verfilmt. Inzwischen waren zwischen den Musikern Spannungen gewachsen. Nach der Veröffentlichung von A Collection Of Great Dance Songs (1981) verließ Rick Wright die Band. Roger Waters nahm mit den beiden anderen Ensemblemitgliedern noch The Final Cut (1983) auf und ging dann ebenfalls auf Solokarriere. Doch der “letzte Schnitt” war noch keineswegs gemacht. Gilmour und Mason beschlossen, Pink Floyd wiederzubeleben, und noch während des Produktionsprozesses für A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (1987) schloss sich ihnen Wright wieder an. Vergeblich versuchte der im Konzertsaal nur mäßig erfolgreiche Waters, dem Trio die Verwendung des Namens Pink Floyd verbieten zu lassen. Gilmour hatte sich längst zum Chef aufgeschwungen und sprach von Waters gegenüber der Presse nur als von „dieser Person“. Die Konzerte der Gruppe zwischen 1987 und 1989 erzielten neue Besucherrekorde in noch mehr Ländern. In der Moskauer Olympiahalle hörten im Juni 1989 30000 Sowjetbürger Pink Floyd. Nach Venedig pilgerten wenige Tage danach 200000. Doch so bereitwillig sich die Fans in die lustvolle Elektronik-Emigration säuseln und donnern ließen, so wenig Gefallen fanden die meisten Kritiker daran. “Die Vernunft ist mit Pink Floyd auf Dauer ausgefallen”, schrieb “Die Zeit” über A Momentary Lapse Of Reason.

“Der Schaden, den die Propheten der selbstzufriedenen Nichtigkeit in der Musik und in den Köpfen ihrer Hörer über die Jahre angerichtet haben, ist vermutlich nicht wiedergutzumachen.”

Nachdem Ende 1989 die Berliner Mauer, Grenzbefestigung der kommunistischen DDR, unter dem Druck mächtiger Massendemonstrationen niedergebrochen war, kam Roger Waters auf den kommerziell stichhaltigen Gedanken, auch seine eigene “Wall” auf dem historischen Terrain des Todesstreifens am Potsdamer Platz in Berlin publikumswirksam noch einmal einstürzen zu lassen. Für 15 Millionen Mark Produktionskosten bot der Pink Floyd-Renegat am 21. Juli 1990 eine All-Star-Cast aus Bryan Adams, The Band, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell, Sinéad O’Connor, Marianne Faithfull, Cindy Lauper, den Scorpions und anderen für nach Polizeiangaben 320000 Besucher auf. Diese “wohnten einem technischen Overkill bei – mit Schweinen aus dem Weltall, einer haushohen Lehrerfratze mit Scheinwerfer-Augen, Militäraufmärschen, aufgeblasenen Multimedia-Effekten und einer kongenialen Sound-Orgie”, notierte der “Stern”, der das Ereignis als “Monument des Größen-Wahns” qualifizierte. Dabei war es nicht nur künstlerisch, sondern auch technisch und organisatorisch ein Desaster. Kritiker Uwe Golz in der “Berliner Morgenpost”: “Für die Mehrzahl der “Wall”-Besucher gestaltete sich diese wagnerianische Veranstaltung zu einer Qual. Die Musiker, Ameisen gleich und genauso groß, tummelten sich auf einer nur erahnbaren Bühne, Videoschirme verwirrten ob ihres schnellen Bildes (die Musik kam verzögert), die zahlreichen Einspielungen und Projektionen auf einer kreisrunden Leinwand und der stetig wachsenden Mauer machten das Sinnlabyrinth komplett.”

Es wurde weltweit live im Fernsehen übertragen. Kritiker Dietrich Leder, der das Ereignis im ZDF-Kanal auf dem Bildschirm verfolgte, im Branchendienst “Funk-Korrespondenz”: “Das Urteil nach den ersten Minuten konnte schlimmer nicht ausfallen: Idee, Konzept, Dramaturgie und Musik von The Wall erwiesen sich als grauenhaft schlecht. Das ZDF trieb einen immensen Aufwand, um mit diversen Kameras die Aktivitäten auf der Bühne aus immer neuen Perspektiven wiederzugeben. Der gelangweilte Zuschauer nahm nur geschäftige Betriebsamkeit wahr.”

Immerhin erzielte die Ausstrahlung auch noch in globaler Entfernung den gewünschten Effekt: Das Original-Doppelalbum von The Wall aus dem Jahr 1979 rutschte noch einmal in die Charts (UK 52, USA 120), die brandneue Konserve The Wall – Berlin 1990 plazierte sich schon im September 1990, zwei Monate nach dem Ereignis, im United Kingdom auf Nr. 27, auf Nr. 56 in den USA. Darüber konnte sich auch David Gilmour freuen, der Waters’ Berliner Wall ansonsten für “schrecklich” hielt. Über das nächste Pink Floyd-Album “The Division Bell”, das mit seinem Erscheinen Ende April 1994 sofort auf Platz eins in die US-Charts einrückte, urteilte “Der Spiegel”: “Was Rick Wright an den Tasteninstrumenten leistet und Nick Mason am Schlagzeug, ist nicht erinnernswert. Gitarrist David Gilmour, der im Konzert so ergreifend ins Leere gucken kann wie O.W. Fischer als Bayernkönig Ludwig II., hat offenbar auch die letzten kreativen Impulse eingebüßt.”

Gleichwohl besuchten mehr als drei Millionen Amerikaner die 59 Konzerte der “Division Bell”-Materialschlacht, davon 52 Konzerte ausverkauft, und gaben 103,7 Millionen Dollar für Tickets aus. Für die anschließende Europa-Tournee, 42 Shows in 16 Ländern, schloß die Truppe einen lukrativen Sponsoringvertrag mit dem Volkswagenwerk, den ein VW-Sprecher ohne Angabe des finanziellen Volumens bejubelte: “Wir haben eine interaktive Methode der Kommunikation mit den Kunden gefunden.” Die Autofirma lieferte eine Pink Floyd-Sonderauflage ihres Modells Golf als Limousine und Cabrio. Die 48 Sattelschlepper, die 700 Tonnen Stahl für die Bühnenkonstruktion, 300 Lautsprecherboxen und eine gigantische Licht- und Laser-Maschinerie durch Europa schipperten, führten auch VW-Transparente mit. Das Stück Marooned von der LP Division Bell wurde im März 1995 als beste Rock-Instrumentalaufnahme mit einem Grammy ausgezeichnet – für Gilmour ein amüsanter Nebeneffekt. Wichtiger war, daß auch die Live-LP Pulse (1995) von der Tournee in England und den Vereinigten Staaten sofort auf Platz eins in die Charts rückte und sich allein in den USA binnen sechs Wochen zweimillionenmal verkaufte. Zwar räumte der Gitarrist im Sommer 1995 in einem “Spiegel”-Gespräch ein, er betrachte “die Menge Geld, die wir verdienen, als obszön”, relativierte aber sogleich: “Wenn man es mit dem vergleicht, was irgendwelche Bosse irgendwelcher Konzerne verdienen, dann meine ich schon, daß mir meine Millionen eher zustehen als denen. Ich habe schließlich der Welt mehr Freude bereitet als Unilever.”

Als 1994 The Division Bell bei der “New York Times” zur Besprechung anstand und keiner der renommierten Musikredakteure diesen langweiligen Job übernehmen wollte, lieh sich das Blatt Dimitri Ehrlich vom Magazin “Interview” als Rezensenten aus. “Stilistisch”, schrieb er, “hätte dieses Album auch schon vor 15 Jahren aufgenommen sein können, was die Würde dieser Musik allerdings in keiner Weise mindert. Man kann der Band nicht vorwerfen, sie sei retro. Pink Floyd haben diesen Stil ja schließlich erfunden.”

Soll sein. Aber bei allem High-Tech-Aufwand konnten sie nicht darüber hinwegtäuschen, daß ihnen mit der Bewältigung der Elektronik keine zeitgemäße Ästhetik gelungen war. Aufs Ganze gesehen, klang die Pink Floyd-Musik kaum anders, als wenn man eine Violinsonate aus dem 19. Jahrhundert auf der Hammondorgel spielte. Im Februar 2000 schätzten Josef Winkler und Arno Frank im deutschen “Rolling Stone” die Band, die 1996 in die Rock and Roll Hall of Fame aufgenommen worden war, nur mehr als “Institution gepflegt-langweiligen Bombast-Entertainments” ein, “für die der Markenname Pink Floyd seit 13 Jahren steht”. Der Rest war wirklich retro. Anfang 2000 erschienen als Re-issue Wish You Were Here – 25th Anniversary Issue sowie das Doppelalbum Is There Anybody Out There? – The Wall Live 1980-81 mit bis dahin unveröffentlichten Live-Mitschnitten sowie zwei Stücken, die auf der Wall-LP von 1997/80 nicht zu hören waren: What Shall We Do Now? und The Last Few Bricks. Zwei unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen der frühen Pink Floyd, Nick’s Boogie und ein Alternative-Take von Interstellar Overdrive, kamen im Sampler In London 1966-67 (2000) der Firma See for Miles in den Handel.

Roger Waters ging 1999 nach zwölf Jahren erstmals wieder auf eine USA-Tournee und führte in kleinen Hallen neben weniger bekannten Solonummern auch die alten Pink Floyd-Heuler auf. Mitschnitte aus Phoenix, Las Vegas, Irvine und Portland mit Andy Wallace (kb), Snowy White (g), Andy Fairweather-Low (g) erschienen im Doppelalbum In The Flesh (2000) – aus purer Geldschneiderei, vermutete Birgit Fuß in “Rolling Stone”: “Neu interpretiert wird jedenfalls nichts, dem alten nichts hinzugefügt. Warum muß immer und immer wieder diese Band ausgeschlachtet werden, bis sie irgendwann jeder haßt?” Derlei wollte sich Roger Waters nicht zweimal fragen lassen. 2001 vollendete er die Partitur der Oper “Ca Ira” nach einem Libretto des französischen Autors Etienne Roda-Gil für die Sänger Ying Huang (Sopran), Paul Groves (Tenor), Bryan Terfel (Bariton) und schwärmte: “Ins Studio zu treten, zuzuschauen, wie die Musiker ihre Instrumente auspacken und mit dem Stimmen beginnen – es ist jedesmal wieder großartig. Wenn 85 menschliche Wesen zusammen die Luft massieren, dann geschieht etwas mit dir. Das ist nicht wie mit dem Computer, der diese Klänge theoretisch auch produzieren kann.”

So könnte es denn sein, daß Roger Waters immer schon die große Oper im Kopf hatte und daß sich der Riesenerfolg von Pink Floyd beim Rock-Publikum im Nachhinein als ein gigantisches Missverständnis entpuppt.

Biography: Remember a Day?

The early Sixties. Everything is up in the air, not least love, drugs and sex. A group of talented teenagers from academic backgrounds in Cambridge — Roger ‘Syd’ Barrett, Roger Waters and David Gilmour — are all keen guitarists and among many who move to London, keen to discover more of this new world and express themselves in it. Mainly in further education — studying the arts, architecture, music — they mix with like-minded incomers in the big city.

In 1965, Barrett and Waters meet an experimental percussionist and an extraordinarily gifted keyboards-player — Nick Mason and Rick Wright respectively. The result is Pink Floyd, which more than 40 years later has moved from massive to almost mythic standing.

Through several changes of personnel, through several musical phases, the band has earned a place on the ultimate roll call of rock, along with the Beatles, the Stones and Led Zeppelin. Their album sales have topped 250 million. In 2005, at Live 8 — the biggest global music event in history — the reunion of the four-man line-up that recorded most of the Floyd canon stole the show. And yet, true to their beginnings, there has always been an enigma at their heart.

Roger ‘Syd’ Barrett, for example. This cool and charismatic son of a university don was the original creative force behind the band (which he named after the Delta bluesmen Pink Anderson and Floyd Council). His vision was perfect for the times, and vice versa. He would lead the band to its first precarious fame, and damage himself irreparably along the way. And though the Floyd’s Barrett era only lasted three years, it always informed what they became.

These were the summers of love, when LSD was less an hallucinogenic interval than a lifestyle choice for some young people, who found their culture in science fiction, the pastoral tradition, and a certain strain of the Victorian imagination. Drawing on such themes, the elfin Barrett wrote and sang on most of the early Floyd’s material, which made use of new techniques, such as tape-loops, feedback and echo delay.

Live, the Floyd played sonic freak-outs — half-hidden by new-fangled light-shows and projections — with Barrett’s spacey lead guitar swooping over Waters’ trance-like bass, while Wright and Mason created soundscapes above and beneath. On record they were tighter, if still ‘psychedelic’. Either way, they sounded ‘trippy’. And perhaps that was Barrett’s intention. He certainly ingested plenty of LSD and other drugs, which didn’t help his delicate mental balance.

Over the spring of 1966, the young band were regulars at the Spontaneous Underground ‘happenings’ on Sundays at the legendary Marquee Club, where they were spotted by their future managers Peter Jenner and Andrew King. And by the autumn, the Floyd had become the house band of the so-called London Free School in west London.

A semi-residency at the All Saint’s Hall led to bigger bookings — at the UFO and the International Times‘ launch in the Roundhouse — as well as the recording of the instrumental ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ with the UFO’s co-founder, producer Joe Boyd. (This track was later used on hip documentaries of the scene.) A signing to EMI followed in early 1967.

“We want to be pop stars,” said Syd. In March, Boyd recorded Barrett’s oddly commercial ‘Arnold Layne’ as a three-minute single. And with a Top Twenty hit to promote, the band took on a gruelling schedule of gigs and recordings.

They appeared at the coolest event of the summer, The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream in Alexandra Palace. They gave a concert under the banner ‘Games for May’ in a classical venue — the Queen Elizabeth Hall — where they displayed their theatrical ambitions through the use of props, pre-recorded tapes and the world’s first quadraphonic sound system. (They received a lifetime ban for throwing daffodils into the audience.) And in June the Floyd released a single originally written for this event.

‘See Emily Play’, which was produced by EMI’s Norman Smith, charted at Number Six and made it on to primetime TV’s Top of the Pops three times (with Barrett acting increasingly strangely). This was followed in August by Pink Floyd’s first LP, The Piper At The Gates of Dawn, which they recorded at Abbey Road next door to the Beatles, then working on Sergeant Pepper. Again making the Top Ten, the album is mainly Barrett’s and is a precious relic of its time, a wonderful mix of the whimsical and weird.

Talking of which, Barrett’s behaviour and output were threatening to bring the band down with him: refusing to speak, playing one de-tuned string all night, writing material like ‘Scream Thy Last Scream, Old Woman with a Basket’. The band wanted to keep their frontman and hoped he would recover himself, so they asked David Gilmour — now back in London after a sojourn abroad — to take over Syd’s role on stage, and thought Barrett might become their off-stage songwriter. They tried a few gigs as a five-piece. But in the end, they decided they could do without Barrett, and by March 1968 were in their second incarnation and under new management.

Set the Controls

Barrett went his way with Jenner and King, and later recorded two haunting solo albums — on which Waters, Wright and especially Gilmour helped — before retreating to Cambridge for the rest of his life. The other four acquired a new manager — Steve O’Rourke — and in a state of some consternation finished their second album, A Saucerful of Secrets (begun the previous year).

Lyrical duties had now fallen to the bassist Roger Waters. And apart from ‘Jugband Blues’ — a disturbing track by Barrett, who contributed little else — the album’s standout moments included the title track and Waters’ ‘Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun’.

This hypnotic epic signposted the style the band would expand on in the Seventies, its vision at first more appreciated by an ‘intellectual’ and European audience. The Floyd played the first free concert in Hyde Park, and laid down the soundtrack for the bizarre Paul Jones movie vehicle, The Committee. They toured continually, developing new material on stage as well as in the studio.

And they worked on the experience, in April 1969 revealing an early form of surround-sound at the Royal Festival Hall — their rebuilt ‘Azimuth Co-Ordinator’. (The prototype, first constructed and used in 1967, had been stolen.) They worked on their concepts, too – at that concert, performing two long pieces fusing old and new material, entitled ‘The Man’ and ‘The Journey’.

So their star continued its inevitable ascent. In July, the Floyd released More, less a soundtrack than an accompaniment to Barbet Schroder’s eponymous film about a group of hippies on the drug trail in Ibiza. The same month, they played live ‘atmospherics’ to the BBC’s live coverage of the first moon landing. In November, they released the double-album Ummagumma, a mixture of live and studio tracks — and that same month reworked its outstanding number, the eerie ‘Careful With That Axe, Eugene’, for Antonioni’s cult film Zabriskie Point.

With Ummagumma at Number Five in the UK charts, and a growing reputation in both Europe and the US underground, the Floyd played some of the key festivals of their time — Bath, Antibes, Rotterdam, Montreux — and between October 1970 and November 1971, put out two more albums.

Atom Heart Mother, their first Number One, featured the Floyd in their pomp — ‘I like a bit of pomp,’ says Gilmour (who also made his first lyrical contribution with the gentle ‘Fat Old Sun’). And Meddle included two timeless and largely instrumental tracks that showcased their lead guitarist in all his vertiginous, keening glory: ‘Echoes’, which took up the whole of Side One and began with a single ‘ping’ created almost accidentally by Wright, and ‘One of These Days’.

Increasingly successful, in 1972 the band was still pushing the boundaries. They shot the film ‘Live at Pompei’ in a Roman amphitheatre, recorded another movie soundtrack for Schroder — Obscured by Clouds — and performed with the Ballet de Marseille. But more importantly, they began to work on an idea that would become their most popular album and with 45 million sold, the world’s third biggest.

Provisionally entitled ‘Eclipse’ and honed through an extensive world tour, The Dark Side of the Moon was released in March 1973, and defies a potted critique here. Demonstrating Waters’ talents as both lyricist and conceptualist, it was also a musical tour de force by Gilmour. But Waters was becoming de facto leader of the band — which in public at least was becoming less about the individuals than the experience.

That was (as Barrett had always intended) increasingly visual. The intriguing sleeve artwork commissioned from the ex-Cambridge outfit Hipgnosis was complemented by stage shows featuring crashing aeroplanes, circular projection screens and flaming gongs. There were backing singers on-stage and a guest slot for another pal from Cambridge, the saxophonist Dick Parry. In the dawning age of stadium rock, the Floyd were truly its masters.

Or maybe its servants? Even before Dark Side broke Middle America through FM radio — with the single ‘Money’ — alienation, isolation and mental fragility had long been Waters’ themes. As a stadium performer, and a cog in the music business machine, he was becoming more prone to all three. As Barrett’s ex-colleague, he had seen them embodied in his old friend. The results were evident in two of his best lyrics — for ‘Shine On, You Crazy Diamond’ and ‘Wish You Were Here’. These tracks were the high points of the Floyd’s next LP, also called Wish You Were Here, which was begun in January 1975 and released that summer.

Famously, Barrett briefly appeared unannounced at Abbey Road during the recording of ‘Shine On’ and shocked the band by his appearance and demeanour. It was the last time any of them saw him — but they were seeing less of each other, too. Personal and musical differences were starting to tell on the band, though it would be several years until these became unbearable — and two more LPs.

Which One’s Pink?

The first was Animals, released in January 1977 (although work had also begun on it in 1975). When this was toured with lavish special effects, including giant inflatables, Waters was dismayed that the crowds kept calling for old hits. In Montreal his patience snapped and he spat into the audience. It was a cathartic moment that gave birth to the Floyd’s most ambitious project ever: The Wall, a largely autobiographical reflection by Waters on the nature of love, life and art.

The double album charts the progress of a rock star, ‘Pink’, facing the break-up of his marriage while on tour. This leads him to review his life from the death of his father – like Waters’ killed on the battlefield before he was born – to his spiteful teachers, his business, even his audience. He sees each as a brick in a metaphorical wall between him and the rest of the world. This wall intensifies his isolation, until he imagines the only solution is to become a fascist dictator. When he confronts his madness and deals with his issues, his torments cease and the wall crumbles.

The show — in which the band were slowly obscured by a giant wall of cardboard ‘bricks’ — was the most ambitious the rock world had ever seen, and was also turned into an Alan Parker film, starring Bob Geldof (who would return to the Floyd story 25 years later). The album sold 20 million, and spawned the band’s only Number One single, the anti-authoritarian ‘Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2’.

Though the album had its musical highlights — Gilmour’s solo on ‘Comfortably Numb’ being the most memorable — it was largely a lyrical piece. Waters drove the project and the others fitted in. They ceded their vision to his increasingly personal direction, and worked together on no new material for more than two years.

When they did get back in the studio, it was to record The Final Cut. This prophetically titled album, prompted by the Falklands conflict of 1982 and released the next year, explores themes of remembrance and the undelivered post-war dream — for which Waters’ father had given his life. Completely credited to Waters, it was attributed to ‘Roger Waters, performed by Pink Floyd’ and featured Gilmour’s vocals on one track.

After three years — during which all four band members had pursued solo projects — Waters announced he was leaving the Floyd and disbanding them. Wright had left the legal entity some time before, transferring to the payroll for The Wall tour and playing no part in The Final Cut, but Gilmour and Mason decided to continue Pink Floyd without its erstwhile ‘leader’. A turbulent period followed, but agreement was eventually reached: Waters would continue to perform the songs on which he worked while he was with the band, as well as new solo material. Gilmour — now first among equals — and Mason would continue to record and perform with Wright as Pink Floyd.

In 1987 came their next album, A Momentary Lapse of Reason — which emphatically proved that the Floyd could exist without Waters. The subsequent world tour, which also spawned the live Delicate Sound of Thunder, was the band’s longest and most successful ever. Over four years, 5.5 million people saw 200 shows, including one on a floating stage in Venice (which again earned them a venue-ban) while Thunder became the first rock album to be played in space, by the Soviet-French Soyuz-7 mission.

1994’s album and tour, The Division Bell, broke similar records; but more, it showed Gilmour and the band on a creative roll, with Wright contributing to some of the writing and Gilmour forging a new writing partnership with his wife, the novelist Polly Samson — ‘High Hopes’ being one of their new classics. However, since then, the Floyd has recorded no new material in the studio.

Not that they have been inactive — nor untouched by sorrows. In 2003, the band’s manager Steve O’Rourke died from a stroke and the three-man Floyd played ‘Fat Old Sun’ and Dark Side‘s ‘Great Gig in the Sky’, at his funeral in Chichester Cathedral. In 2006, Syd Barrett died from pancreatic cancer. And in 2008 Rick Wright followed him — but not before he had helped re-write the Pink Floyd story a couple more times.

In 2005, prompted by Bob Geldof, the band decided to perform at Live 8 (on the 20th anniversary of Live Aid) and invited Waters to join them. He accepted and — sharing vocals with Gilmour — they played two numbers from Dark Side, plus ‘Wish You Were Here’ and ‘Comfortably Numb’. It was an epoch-making moment in rock history, and their final group hug became one of Live 8’s iconic images.

After that, the three-man Floyd performed together on two occasions — once during a solo gig by Gilmour in 2006 (Wright played the whole three-month tour and was ‘in great form’, says Gilmour); and again at an all-star memorial tribute to Barrett in 2007. Waters also appeared at the gig but was unable to join his old colleagues due to a previous appointment. Still, that was not the end of their association.

On 10 July 2010, with some of their favourite musicians, Waters and Gilmour performed a few Floyd songs — plus Phil Spector’s ‘To Know Him Is To Love Him’! — at a private charity event in Oxfordshire. And on 12 May 2011, during one of Waters’ Wall concerts at the London O2, Gilmour appeared on top of the wall as of old, to sing and play his parts on ‘Comfortably Numb’. Nick Mason, who was at the gig, then joined them for the final song, ‘Outside the Wall’. Departing the stage, as they had before, Waters played trumpet, Gilmour mandolin and Mason tambourine. The audience was stunned and delighted.

But a handful of concerts was never going to sate the interest of the diehard fans. In 1995, they were rewarded with the double-album P•U•L•S•E, all recorded on the Division Bell tour and containing the first complete live version of Dark Side. A live compilation of The Wall from 1980-1 — called Is There Anybody Out There? — followed in 2000, and then a re-mastered ‘best of’, called Echoes. There have also been collectors’ editions of Dark Side, a complete works box-set — Oh, By the Way — and now (autumn 2011) an extensive reissue campaign by EMI, with new packaging and production values, not to mention some rare and archival recordings that go back to the Barrett days.

Nor, as individuals, have the survivors from those times been strangers to the studio or stage these last dozen or so years (and before). Gilmour put out his third solo album, On an Island, in 2006; Waters has had a prolific and varied career since 1986; Mason and Wright released one or two collaborative albums respectively.

There have been awards and honours along the way: induction into both the US and UK Rock ‘n’ Roll Halls of Fame; Sweden’s Polar Music Prize in 2008 for their ‘monumental contribution over the decades to the fusion of art and music in the development of popular culture’. And in 2010, The Royal Mail used Division Bell visuals on their stamps, also creating a unique sheet using only the Floyd’s imagery.

So is that the end of the Floyd’s road? Do they still exist? Yes, they do.

Source: Pink Floyd.com

Roger Waters

Ex-Frauen: Judith Trim, Lady Carolyne Christie, Pricilla Phillips (Frankie and Johnny), Laurie Durning,

![Wish You Were Here (50th Anniversary) [Vinyl LP]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fZFGuVxVL._SL160_.jpg)

![Wish You Were Here (50th Anniv.) Deluxe Box [Vinyl LP]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41Aitr1IzEL._SL160_.jpg)

![Wish You Were Here/Coloured Vinyl [Vinyl LP]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41x2vN9YBFL._SL160_.jpg)